About BC: BC, also known as soot, is formed during high temperature fuel combustion. The major source of BC in the U.S. is diesel vehicles. In Pittsburgh, there are also significant emissions from industrial facilities such as coke ovens and steel mills.

Regulation and attainment: BC is a component of fine particulate matter (PM2.5). The EPA designates PM2.5 as a criteria pollutant, and there are two standards: an annual average standard of 12μg/m3 and a 24-hour standard of 35μg/m3. The World Health Organization (WHO) advocates for even lower standards that would better protect health: 10 μg/m3 annual average and 25 μg/m3 daily average. The annual and daily standards reflect the fact that PM2.5 exposure has both chronic (e.g., death) and short-term (e.g., asthma attacks) health impacts. Allegheny County does not meet either the annual or the 24-hour PM2.5 standards. BC is not regulated directly by the EPA, but it contributes to the particle problem in Pittsburgh.

Health: Exposure to PM2.5 is connected to a variety of health impacts: increased asthma attacks, heart attacks, lung cancer, and death. Fetal exposure to PM2.5 leads to low birth weight and some studies have also linked it to the development of autism. PM2.5 is a complex mixture of thousands of components, and thus most studies of PM health effects have focused on total PM2.5 exposure. However there is emerging evidence that certain PM components, including BC, are particularly harmful.

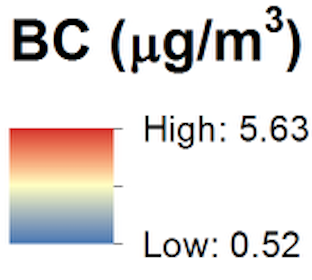

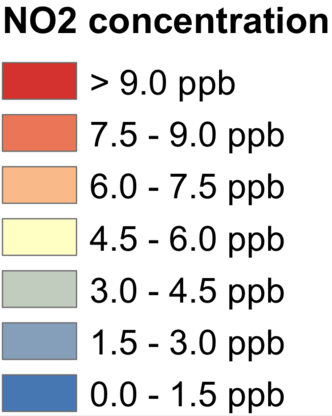

At-risk individuals: At risk individuals can also include those with chronic conditions (heart or lung disease, diabetes, etc), the very young, the elderly, and women of childbearing age. In Pittsburgh, BC concentrations are the elevated near roadways, near industrial areas, and in the river valleys. People who live and/or work in these areas can be exposed to BC concentrations that are a factor of 4-10 higher than the concentrations observed in upland areas located far from major roads or industrial facilities.

What can be done: The benefits to regulating BC emissions are huge. In the United States, the average public health benefits associated with reducing directly emitted PM2.5 (such as BC) are estimated to range from $290,000 to $1.2 million per ton PM2.5 in 2030, according to the U.S. EPA. Large industrial sources in Pittsburgh can emit more than 10 tons of BC per year. The cost of the controls necessary to achieve these reductions is generally far lower. Diesel trucks and buses should follow the existing anti-idling laws, which reduce emissions when the vehicles are not in motion. School districts and transit authorities can trade out old buses for newer, cleaner models or retrofit older vehicles with pollution control equipment such as diesel particulate filters. Perhaps most importantly, emissions from industrial facilities can and should be reduced. Mobile sources like cars and trucks are the major source of BC emissions in the U.S., but emissions from this sector have been falling much more rapidly than industrial emissions.

Limitations of this study: (1) The map shows annual average concentrations, and therefore smoothes over shorter plume events that occur periodically and could cause acute health impacts or odor complaints. (2) BC is just one measure of carbon soot particles in the atmosphere. One can also quantify "elemental carbon", or EC, which is measured differently than BC and can therefore produce different concentrations. (3) While there may be limitations or uncertainty in the absolute pollutant concentrations represented by the maps, the gradients and spatial variations are a good representation of reality. Areas colored red have higher concentrations than areas colored blue.